![]()

**CONTAINS ALL THE SPOILERS**

I write this post for feminist parents who may have wondered if this show is good to show to their adolescent daughters, given that Rory Gilmore is a rare example of a fictional TV teenage girl who studies hard, is smart, and is nice to people.

I watched Gilmore girls because a lot of other people like it. This from Chuck Wendig:

“Have you seriously not watched Gilmore Girls? You are dead to me. One of my top ten favorite shows. Smart, snappy, sweet. Like Buffy but without all the vampire-slaying. Like Veronica Mars without all the… detecting? Whatever, shut up, just go watch it.”

I was a little old for Gilmore girls when it first aired — I would’ve loved it around age 14 — and by the time I got to it (last year) I was already older than the character of the mother who is, admittedly, young at 32. I had seen a few scenes here and there — maybe I even saw an entire episode at one stage — and had found it generally annoying in an unidentifiable way. Then I realised there’s a bit of a Gilmore girls resurgence on, or maybe it never really went away, and I found myself reading stuff like this:

A Fan’s Notes On Gilmore Girls from The Awl.

So I thought it might be a nice thing for a mother and daughter to watch together, even though my daughter is a little young. So we started watching it. When her interest waned I kept watching, so now I have watched it. I have watched all the Girlmore girls. I watched it because there isn’t all that much out there which is made for girls, about girls — non-messed up girls. Girls who don’t hate their mothers most of the time. Girls who don’t exist on screen in order for the audience to hate on them. Rory Gilmore characters are rare on screen.

Here are the good bits in a nutshell:

- I enjoyed the 90s and early 00s references (which would now mostly go over the heads of a younger audience).

- Fast-paced dialogue. I may have a high tolerance for dialogue-heavy stories. My husband says he doesn’t know how I can follow what they’re saying, even though he likes Reservoir Dogs. Apparently, he doesn’t catch a single word of Gilmore girls.

- I most wanted to sit down in front of Gilmore Girls when I was feeling tired or had to do the ironing. On a particularly stressful day, I watched about three episodes in a row. Stepping into the world of Stars Hollow is like stepping into the world of Sylvanian Families, right down to the omnipresent

kebab-shop fairy lights and small-town concerns, and the fact that even when the weather is ‘bad’ it is still really, really beautiful, Stars Hollow is pure fiction and therefore borders on cozy fantasy. It should probably be considered suburban fantasy, because Stars Hollow is not really much like real life. For starters, there isn’t really much in the way of ethnic diversity. That’s not how I think of America, but then, almost entirely white towns with a token black Frenchman and token Asian families run by tiger-moms may well exist in Connecticut for all I know.![Lorelai's House, Gilmore Girls]()

IS GILMORE GIRLS STILL GOOD FOR GIRLS?

A GG fan writing for The AV Club has provided a full summary of the first two shows though, as ever, your best bet is by simply watching. Gilmore girls is available on iTunes, and costs less than a lot of other shows, at less than a dollar per episode.

I do have some nagging concerns about this ostensibly feminist show. The first is my usual concern: That a young audience doesn’t necessarily know what’s irony and what’s not.

![Funny Gilmore girls quote. Love this. My dr told me today that it's better to look good then feel good! LOL he didn't know the Gilmore's already explained that.]()

And here are some other thoughts.

1. ANTI-HEALTH-FOOD MESSAGES

Look at it one way and you might conclude that Gilmore girls is a show which depicts a range of body sizes. Compare the Gilmore girls to Melissa McCarthy’s character, whose overweight presence in Hollywood is a constant reminder that anti-fat messages pervade modern culture, especially for women.

But we should look a little further than that. I’m going to argue that Lorelai Gilmore is a strong candidate for an eating disorder not otherwise specified. In Season Six, after Rory moves into the tennis house, Emily says to Rory (partly in jest), ‘You’re not bulimic, are you?’. Rory shrugs it off as ridiculous but I had been wondering the same thing in earnest for quite some seasons by that stage.

(I’m not the only one to have noticed this.)

An entire movement has popped up, in response to the horrible body-checking and anti-fat movement which women have been subjected to since forever sometime last century, depending on your culture. I happened across this inspirational poster on Pinterest and it pretty much sums up the culture I’m talking about:

![Eat cake for breakfast]()

This is certainly one way of dealing with the anti-fat, dubious health warnings we (and in particular, women) are subjected to every single day. I happen to think sugar and transfats are so harmful that our family has given them up entirely, and this informs my opinion, naturally. Turns out Alexis Bledel thinks along the same lines. In an interview she was asked about her diet, because women in the spotlight always are:

How often do you prepare your own meals?

Almost every day. I try to eat very healthy, organic, local foods, so I do end up preparing my own meals more often than I go out. I prefer to go out for a drink because in that case you pretty much know what’s being poured into your glass, as opposed to what’s going into your food.

- Alexis Bledel’s Mortal Enemy Is the Lat Machine at the Gym

Western cultures everywhere have now got to a point in food history where eating nothing but fast food is about as funny as any other kind of addiction. I.e. not very. (Jezebel fairly recently asked if sugar is the next booze. I say yes.)

![Gilmore thought process]()

Lorelai Gilmore, the character, has responded to the anti-fat messages of the 80s and 90s by rebelling against her mother (who by the way, also can’t cook) and also against society in general. She takes bad eating to an extreme, and it forms the basis of a gag in pretty much every episode.

![What are we if not world champion eaters?]()

Lorelai does not keep food in the house, including good coffee, which is partly an excuse to visit Luke at the cafe, but nor does she know how to cook. Lorelai is your stereotypical flighty female who drinks too much coffee for her adrenal health, and prides herself on eating sugary food full of transfats until she feels uncomfortably full, swaggering around clutching her gut.

It’s time to move past this now. A fully functioning human being knows how to boil an egg, women included. Failing to learn the basics of cooking is about as cool as failing to wipe your own backside. It’s not a feminist statement anymore, to support the fast food industry by refusing to keep whole foods in the house. But there’s more to my gripe than that, because after all, Lorelai is an imperfect mother and deliberately written that way.

The bigger problem is that the bad eating habits of Lorelai and Rory Gilmore send an erroneous Maybelline-esque message to all the young women out there who think that looking like Lauren Graham in your thirties is a matter of genes and good luck:

![]()

from 1991

Looking like Lauren Graham has nothing to do with luck, however, and everything to do with ‘being on a diet since the age of 11′. Does the actress who plays Lorelai Gilmore really eat like this? All I needed to do was google lauren graham diet and I got the answer I expected:

“One thing I’ve learned is I actually don’t like variety very much,” she told SELF. “I like having the same thing over and over: assorted lean proteins, arugula salad, quinoa or brown rice with soy sauce, olive oil, lemon and salt. Those ingredients can pretty much get me through the week.”

From US Weekly:

Since the age of 11, Parenthood‘s Lauren Graham has been watching what she eats. “I’ve been on a diet for 35 years,” the 46-year-old TV star reveals in the May issue of More.

Melissa McCarthy’s character, Sookie, has a far more healthy relationship with food, even if she is more prone to showing the outward signs of insulin resistance. She loves food, prepares it well and along with Jackson, who knows his fresh produce, is no doubt far less vitamin and mineral deficient than Lorelai and Rory.

Speaking of Maybelline, or makeup in general, we never once see any of the female characters without their maquillage. Emily, Lorelai, Rory and even the more down-to-earth Sookie are consistently depicted in full makeup, with not one scene taking place in front of a mirror in which said makeup is applied. There are occasionally scenes in which characters wear even more makeup than usual, such as when Rory sneaks out of her grandmother’s house to see Logan and hopes her grandmother doesn’t see her dark eyes and red lips, but let’s not be fooled into thinking that the less colourful faces of these actresses are somehow makeup free, even first thing in the morning. Perhaps in a town like Star’s Hollow it really is unheard of to spend waking hours without makeup (and also mornings in bed with male partners), but this whole thing smacks to me of another kind of beauty deception. I say this even though there is no place on the planet that looks more like a Sylvanian Families marketing shoot than Star’s Hollow, where everything looks perfect all the time, because honesty about female beauty is more important than ever.

![I love Gilmore Girls!! If I ever have a daughter I might even name her Lorelai :)]()

![… loin-fruit that she is, straggled out of bed to grace me with her presence? But then I asked myself, "WWTBFCD?", and it came to me in a flash: I'm gonna make waffles! "What would the Barefoot Contessa do?". Exactly. Barefoot's one word. Shut up, loin-fruit. haha]()

The closest we see to disheveled is mussed-up hair

Here’s another thing saying pretty much this, about Sex and the City and a bunch of other shows which depict healthy looking women chowing down on junk food: The Myth Of Eating Actresses — And Why It’s Dangerous For Women from The Frisky

![Gilmore Girls]()

In the first episode of Season Seven, Lorelai and Rory very uncharacteristically go to play ‘racquet ball’ (an easier version of squash?) but they don’t actually play — they sit on the floor and talk, like petulant teenage girls on strike during high school gym class. When two men walk into the room wanting to have an actual game, Lorelai tells them to go away — they’ve booked it for an hour.

As a fan of certain racquet sports, I find this behaviour extremely annoying. There are only a certain number of courts in the world, and people who don’t want to make actual sporting use of them should go home. To me, that scene feeds into stereotypes about girls and sport.

2. LACK OF AWARENESS OF THEIR OWN PRIVILEGE

I’m sure a lot has already been said about this: a story about rich white people living in the sort of fictional town which… well… really only exists in fiction. This is easy to criticise. I mean, in real life you don’t have a a busker creating music to the soundtrack of your very own internal dramas. In this sense, Gilmore girls is metafictive. The world does need way more stories about non-white people, granted. Should this be the show to do it? Probably not. The depictions of Lane’s Tiger Mom are stereo-typically Asian and we never do see Mrs Kim as a rounded character; she exists purely for entertainment. Ditto Michel Gerard, the concierge who works closely with Lorelai at the hotel. He is aloof and style-conscious in a stereo-typically French kind of way. This show isn’t about breaking into non-white subcultures.

What this show could do better, though, considering the age of its intended audience, is show some self-awareness of the privilege of its main cast.

For instance, there is an episode near the end of season one in which Lorelai takes Rory to taste test wedding cakes. It later emerges that she has no genuine interest in buying a wedding cake — she is only interested in sampling all the different flavours, for free. This isn’t said, but she’s doing this at the small-business owner’s expense. So although Lorelai Gilmore ran away from her privilege, finding it more stifling than helpful, she has the looks and the breeding and the skin-colour to fit neatly into a secure and fairly well-paid job at the hotel, and although the audience is reminded regularly that this was through Lorelai’s own sheer hard graft, in the real world, there was more to it than that. Lorelai Gilmore has the right accent and the right looks for running an inn, and no amount of hard graft is going to help many, many more women around the world working as hotel cleaners work their way into management by their early thirties.

![gilmore!]()

I honestly don’t know if this is irony. Because yes, Lorelai Gilmore can (and briefly did).

The wedding cake taste-testing incident shows that Lorelai Gilmore lacks the moral compass to steers decent folk away from taking advantage of someone else’s time, even if that someone is a seemingly unimportant middle-aged woman who works in a wedding-cake shop.

![]()

Lorelai Gilmore completely misses the point.

In season five, episode fourteen, Rory borrows Logan’s limo and chauffeur to make an emergency trip to Stars Hollow. Upon returning the vehicle, she informs Logan that she ‘fed Frank a sandwich’, as in ‘I filled your car with petrol,’ or ‘I fed your monkey some nuts’. Did I need to mention that Frank is black?

Naturally, for those who watch further, the audience sees repercussions for privilege. Logan is indeed a problematic person whose own bad manners and gilded cage cause him grief. For the younger members of an audience, it’s perhaps worth pointing out the obvious.

That’s also why it’s important to keep watching until Season Six, where the theme of privilege and excess comes to a head. It feels at this point that all of what has come before has been in the sole aid of exploring what it means to be white and young and bright and pretty.

On the topic of Rory’s dropping out of Yale, I feel this failed somewhat in the narrative sense. It was too sudden. After watching five entire seasons of the strong-willed, kind, ever-sensible Rory Gilmore breeze through difficult social situations, offering wit and wisdom to her classmates, to suggest that the comments of one man could derail the plans she’s had for her entire life is not believable. In order for me to believe this of Rory, I needed to see more build-up. I needed to see increasing frustration with her life at Yale. I needed her to perhaps see through the bullshit privileged environment she found herself in. But no, Rory is mysteriously allured by Logan. I wonder if a younger audience has a problem with this love story. I find it unbelievable that a girl like Rory, who has seen both privilege and near-poverty (apparently) in her own family situations, would fall for Logan.

When Rory and Logan steal a yacht (at Rory’s suggestion) the idea of privilege is consciously explored when the judge expresses disgust at rich white kids using the world as their private playground, thereby increasing the number of community service Rory is required do. I feel a sense of unease that Rory’s misdemeanor raises her status among Logan’s friends, who throw a huge party in her criminal honour, each one of them dressing up in stripes. (Not far enough from the underprivileged version of ‘black face’, I feel.) When the camera is on Rory at her community service, the glossy cinematography of Stars Hollow doesn’t fit at all; nothing of the underclass is evident even though she is surrounded by those less privileged than herself. She is soon ordering the others around and they are (completely unbelievably) doing just as she tells them to do. Has she learnt anything at all from this experience? More importantly, has the young viewer?

![]()

In Season Six, even the privilege of Paris Geller is challenged after the tax office catches up with her parents. Paris becomes temporarily impoverished, which leads her to seek work in a kitchen at one of Rory’s events with the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution), during which Marx suddenly makes complete sense to her. This article reminded me of that scene.

3. modelling of bad manners

When main characters do bad things, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. After all, the age of the Mary-Sue is over. I find it admirable that Rory Gilmore is written to be an excellent role-model who gets into three top universities through sheer diligence, and demonstrates her intelligence regularly by offering balanced commentary which is wise beyond her years. Such kids do exist. It’s hard to write a character like Rory Gilmore without fans eventually growing to hate her. Rory makes just enough mistakes.

The older Gilmore girls are a different matter. Emily Gilmore (as well as Richard Gilmore — by season four) are monstrous creatures, and I say this even though Emily Gilmore is strangely likeable, or perhaps just nice to watch. In a show designed for a tween audience, that’s okay, because at no stage is the audience invited to identify with either of the grandparent characters. The show is unquestionably about Lorelai and Rory.

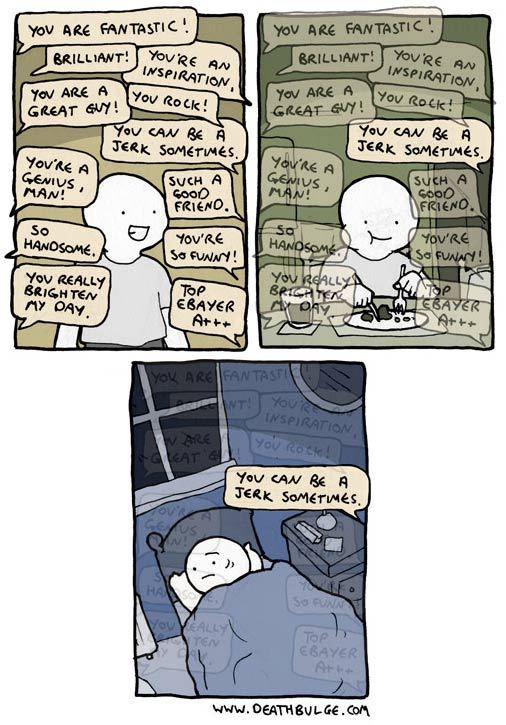

But when Lorelai demonstrates bad manners and these bad manners go either unchecked or rewarded, this is another issue. The reason I consider this important is because Lorelai Gilmore is so obviously written to be a role model for viewers of adolescent age: a young, hip, fast-talking mum of the kind that exists in fantasy — the kind who is a teenage daughter’s best buddy. If you’re in any doubt about the power of a character such as Lorelai Gilmore, read this from a twenty-five year old fan of Gilmore Girls who has only more recently come to understand the character’s many shortcomings:

The show became a part of my identity, and also something sacred. A biblical text.

1. Lorelai Gilmore talks loudly and incessantly through every town meeting, every speech and even throughout someone’s funeral. Although she gets shushed quite often, this is always by a pesky old man character. Lorelai giggles and keeps on doing this. It reminds me of assemblies at a girls’ high school.

![Gilmore Girls and Freaky Friday]()

2. Lorelai’s ability to manipulate men with flirtatiousness. During another funeral procession, Lorelai rushes up to the family member who has inherited a building and asks if she can buy it. Carrying the coffin, he asks if they might discuss it later. Lorelai ignores his request and continues to harass the man. In the gets what the building she wanted, she and Sookie open their inn, and because this has been a longterm goal that the audience has been invited into caring about, to the viewer it seems she has got what she wanted because she was pushy and inconsiderate. I suppose this is a real-estate lesson in its own right. It’s also one you might want to discuss with your young co-viewer.

![Gilmore Girls]()

3. Lorelai does not respect Luke’s ‘no’. A stunningly uncomfortable example of this happens at the beginning of Season Four, as Lorelai sets Rory up at Yale. Since Lorelai is overly-interfering in her daughter’s life (something so obvious I don’t need to go on about it at length here) that she insists Rory get a new mattress. Lorelai has arranged to borrow Luke’s utility van but Luke has said to get it back to him by a certain time, because he needs it. Of course there are mattress related dramas at Yale, and Lorelai ends up bringing home a second-hand mattress… late. Not only has she returned Luke’s vehicle later than he wanted, but she tries to get him to store the old mattress. Throughout that episode the perennially grumpy Luke continues to say no to Lorelai, and Lorelai continues with her pouty, ditzy act that attractive women of child-bearing age can often get away with, playing on the sexual tension that runs between Lorelai and Luke from the pilot episode. It might be worth explaining to a young viewer that good relationships happen when each partner respects the other. If you’re friends (or proto-lovers) with someone and you keep saying no and somehow you end up doing the thing you said no to, over and over again, that ain’t a good relationship. Saying no should be normal.

![]()

4. Lorelai actually doesn’t know when to shut-up. This is a big part of her quirky personality, and it’s part of what makes the scripting of Gilmore girls unique. But most of the time the audience is encouraged to find Lorelai’s outbursts cute rather than downright inappropriate. Let it not be said that Americans don’t do irony; Lorelai Gilmore has sarcasm in spades. At times Lorelai says what we all wish we could say, and at other times I feel the audience is invited to be complicit in a bitchy comment (about AV geeks, about someone’s clothing choice, about Kirk in particular) and I’m not sure a young audience is encouraged by the show itself to know the difference.

![@Heidi Harris Someone needs to print this and frame it for Granny!]()

4. stock characters who simplify complicated real life issues

What you get from Gilmore girls is a cast of hyperbolic characters. Every one of them has a stand out characteristic which makes them unique (though there is a disproportionate number of characters with OCD type quirks).

On screen fiction tends to tell the stories of the outward signs of OCD but more seldom gets into the darker, internal side of obsessive compulsive thoughts. Perhaps this is a failing of the screen compared to the novel. The difference is summarised here by Jody Michael.

Below we have the three girls most significant at Rory’s high school. When I first saw these characters, on Rory’s first day at Chilton, I was a little disappointed. First we have the overdone ‘mean girl’ — Paris, who does get more interesting as the series progresses. Paris is also a great example of a perfectionist who is so hell-bent on getting what she wants she ends up sabotaging her efforts. A lot of super-bright girls surely find themselves in a similar position. As a case study, Paris is fascinating.

The other two (Louise and Madeline) are ditzy rich girls who go boy-crazy after graduation. If this were a slightly more nuanced show, the relationships between these girls could have been written in a far more interesting way. Might tweens have got more out of Rory’s relationships with these three had the interactions been as nuanced as, say, the relationship between Lorelai and Luke, or Lorelai and Rory, or Lorelai and Emily? Instead, these relationships provide nothing more than a jump-off point into a range of bullying related issues, but the show itself does not offer the nuance; that’s up to the viewer. In real life, bullies do not always stand out a mile. Bullies are not always pretty. Most kids are bullies at least some of the time (including Rory, I might add, when she speaks disparagingly to the AV Guy). Bullying changes shape in senior high school. In this story, the overt nastiness typical of junior high school relationships continues through to the end of these girls’ time at Chilton. This doesn’t ring true.

There are still too few stories about the real nature of high school cliques, even though there are plenty of black-and-white mean girls in literature.

![Gilmore girls]()

5. a show with female protagonists isn’t necessarily all that accepting of women

In one of the earlier seasons, Luke is disgusted by a woman breastfeeding her baby in his cafe. Sure, Luke is disgusted by all sorts of things: children in general and mobile phones in particular. This makes for an interesting plot line when it turns out he has a 12 year old daughter. But the joking way in which Lorelai and Rory react to Luke’s disgust make them borderline complicit. Since there is plenty feminist of discrimination of women breastfeeding in public, anyone au fait with the disconnect between utility and the fetishization of the female breast may well feel uncomfortable with this particular scene.

In episode two of season five Lorelai makes disparaging comments about attending a venue full of women who had not shaved their legs. In Gilmore World, absences of grooming go punished. In the same episode, Lyndsay’s mother approaches Rory in the street and accuses Rory of being a homewrecker. At no point in that same episode is it said that it was not Rory who was married, and therefore Dean’s own fault for breaking up his own marriage.

By the way, there are a lot of jokes about prostitution.

![Gilmore Girls]()

![tumblr_m9afkamBF91qgmul2o1_250.jpg 250×350 pixels]()

I mention this not because I want to shield my daughter from knowing anything about the darker side of life, but because I don’t want my daughter to think, in a superior fashion, that being a ‘whore’ is somehow the best of all insults. That’s a long story, but suffice to say, using whore as an insult is not a very kind thing to do in a world where human trafficking is a huge problem, where lots of countries don’t look after their women and girls, and where the demand for female prostitution is as strong as it ever was in a world where we like to think women make ‘bad choices’.

Explain that one to a tween. Because all she’ll see is that ‘whore’ is an insult. Along with ‘slut’, and similar, with the flip-side being that virginity is a special prize.

To sum this issue up, this show is about women and contains a lot of feminist messages, but feminism has evolved a little since the mid 2000s.

(Bad Reputation blog has an interesting series of posts about widows, and Paris Geller gets a mention.)

6. traditional views about sex and relationships

To follow from the previous point, if you’re after ‘traditional’ for your tween daughter, this is what you get from Gilmore girls. What you may not get is ‘healthy’ and ‘progressive’.

Everybody’s scared of teenage girls, especially when they have sex. That’s well-known. “I’ve got the good girl,” Lorelai says to herself after over-hearing Rory admit to Paris that she never had sex with Dean. The implicit message is that Paris is the ‘bad girl’ for having sex with a boy… in her final year of high school.

What they are talking about is p-in-v sex, we presume. Until the end of season four, we only ever see Rory kissing, and I think it’s worth mentioning that we only see Rory kissing awkwardly. Alexis Bledel manages wordy scripts with ease, but where she does not shine as an actor is in any scene that requires intense emotion. She always looks supremely uncomfortable with her boyfriends. This makes me wonder about the ethics of asking young actors to perform in this way. The discomfort is so palpable that I wonder about the message: If Rory doesn’t seem to be really, truly enjoying the physical intimacy with her boyfriend, but has boyfriends anyway, are teenagers of high school age nevertheless obliged to make these relationships, even if they are bookish types?

The seasons get slightly more adult in theme as the viewers themselves grow up. When Rory loses her virginity (off-screen), the post-coital scene with Dean is as awkward as any ever were. The Event of Virginity Loss is a big plot point in any story for this audience, but I’d like to see a cultural shift in focus. Why was the break-up of Dean’s marriage resting upon the puncturing of Rory’s hymen? Why wasn’t the marriage considered over before that, when it was clear that Rory and Dean had a close emotional connection? Something to discuss with young viewers is the murky definition of ‘cheating’ and ‘affairs’. How much weight do we as a culture heap upon simple physical acts? Is ‘virginity’ really that important? What counts as sex? Bill Clinton started that big conversation. I hope progressive culture has moved a little since Gilmore girls first aired, and that this storyline will continue to date badly. By Season Six, this emphasis on purity is questioned when Emily and Richard arrange for their Reverend to give Rory a talk about saving her ‘gift’ for one special man. Rory handles this with aplomb. (This is another reason why it’s important to watch Season Six.)

Rory’s third sexual partner is Logan. Gilmore girls continues to keep any actual sex off-screen, to the point where adult viewers might feel the relationship between Luke and Lorelai a little weird (though I can imagine it was a little weird for the actors, too, working with each other for several seasons before having to pretend intimacy. I don’t think I’d like to have to do sex scenes with a guy I’d been working with for four years.)

On the topic of Logan and Rory, it happens in Rory’s room at Yale. This scene could be the catalyst of an important conversation about consent with your adolescent daughter. Because as things between the two characters heat up, Logan says to Rory something along the lines of, ‘If you want me to leave, you’d better tell me now.’

This line is used a lot in fiction, and because of that, I’m guessing it’s used a lot in real life, too. (Robert Kincaid says it to Francesca in The Bridges of Madison County, for example.)

A problem with this sentence, when used by one partner to indicate that (or ask if) sex is about to happen, is that it suggests an uncomfortable subtext. When Logan says this to Rory, it sounds a lot like, ‘If you don’t want sex then you’d better tell me to stop now, because I’m about to get so caught up in the heat of it that I won’t be able to stop at any point between now and completion, so if you don’t want the full menu, tell me to leave now.’ That is an ultimatum of sorts.

But actually it doesn’t work like that, does it. In fact, boys are fully capable of controlling themselves (if they want to), and a girl can negotiate from the full range of possibilities; sex is not an all-or-nothing proposition. When a boy (or a girl) says ‘If you don’t want this, tell me to leave now,’ it can sound creepily manipulative.

Other aspects of the sexual side of relationships are explored to a certain extent, and viewers will each make their own minds up about that. Rory experiments with an open relationship but when Logan decides he doesn’t want this, Rory is happy to drop everything for him.

Lorelai sleeps with Christopher after her second break-up with Luke, as a way to confirm to herself that her relationship with Luke is over. As a consequence she ends up using Christopher, and conveys to a young audience that this is one way of ending a relationship for good. Oh, and Luke storms round to Christopher’s house and sucker punches him. In real life, this can kill. Is it a teenage girl’s fantasy to have boys fight over her in this fashion? Should it be? Lorelai to Luke in the middle of the street: ‘Next time you get a hankering to punch someone’s lights out, take your anger out on me. I’m the one who deserved it.’ (I’m pretty sure she didn’t mean physically, but nor was it clear that she didn’t.)

7. PRODUCT PLACEMENT and consumerism

As the seasons progress, we see more and more product placement (or perhaps I just never noticed it in the first few seasons). I wonder how much Birken paid for the episode in Season Six where Logan buys Rory a Birkin Bag. This is a bag which Emily has wanted her entire life. It’s talked about, a lot.

![]()

The actor who plays Logan is very good, capable of expressing both stoned boredom and strong emotion.

In an earlier episode (Season Five, Episode 20), there is a scene before the opening credits in which Rory and Lorelai each watch their robot vacuum cleaners. Rory is at Yale and Lorelai is in Star’s Hollow. They are sharing a moment. This is probably the scene which smacks most strongly of product placement. It feels just like an advertisement for robot vacuum cleaners. (We don’t see them again.)

Like almost everything ever, we also see Rory working on an Apple laptop in her room at Yale. I wonder if someone on the set wanted a new Apple laptop that week?

![Rory Gilmore and Apple Inc. Photograph]()

Ah, remember when Apple laptops were this huge? With colours?

I don’t think product placement is in itself a huge problem, and if you’ve made the decision to watch TV, you’re probably highly aware of it. But it’s something I would point out to a young viewer as part of media literacy.

The consumerism of the Gilmore girls, on the other hand, is over-the-top. When Lorelai orders fast food she orders enough for a football team (or perhaps a TV camera crew?). When the Gilmore girls go shopping they really go shopping. This would be realistic enough, I guess, if Lorelai were not a hotel manager, which would certainly pay enough to live a comfortable lifestyle (at least in this country) but not enough to waste money on ice-creams in winter before deciding it’s too cold for ice-cream and dumping it straight into the bin. Throwing food and goods out on a whim is a luxury most of the world does not have. And even if they did hypothetically have it, the environment cannot sustain that attitude towards material items.

Then there’s the unresolved issue of Lorelai’s borrowing a significant sum of money from Luke when she opens her own inn. Are we to assume she has paid it back before we see her jump straight back in to her wasteful spending? After breaking up with Luke (again) she throws out everything that reminds her of Luke, including a waffle maker because Luke made waffles. We never find out if she has paid Luke back.

8. ON THE SORE TOPIC OF SEASON SEVEN

I’d been prepped on this because The Internet does not collectively approve of season seven. A ‘truly stale Pop Tart’, even.This is the season that Sherman-Palladino did not write. Fans of the show saw a distinct change in tone and didn’t like how the plot progressed.

But since I’d basically been hate watching the first six seasons, I wondered if I might suddenly like the seventh? How’s that for logic?

I immediately detected a change in tone. When Kirk ploughs into the side of Luke’s diner, Rory’s retelling of the incident to Lorelai shows an uncharacteristic lack of empathy for Luke, who inherited the building from his father. Likewise, it’s not like Rory to be reflecting nauseatingly about what Logan’s gift of a rocket meeeeans for their relationship. The pre-season-seven Rory Gilmore would not have pretended to know its significance when her absent boyfriend calls to ask if she ‘got it’ (the rocket and the joke). This is especially infuriating after six seasons (almost — apart from her reason for taking a break from Yale, which was also out of character) of Rory Gilmore being the level-headed, wise one.

Do the new writers really get the character? Even her dialogue sounds a bit more ‘Valley Girl’ (as it’s apparently known), with more ‘likes’ and ‘I mean’s and various hedge phrases. Why? Why do this, when the fast-paced witty dialogue is really the thing that makes this show standout from various others on the Disney channel? This was especially obvious in Rory’s first scene in episode two of this season, as she complains to Lorelai about how much she wanted to travel the world (presumably on her boyfriend’s money), but her rich boyfriend doesn’t want to see her until Christmas. Rory even says ‘Oh yay’ and ‘Nutso!’ to which Lorelai responds ironically ‘Spoken like a true grown-up’. I sense from this counter dialogue that the writers are aware of what they’re doing to Rory, but they’re doing it anyway. After a while the dialogue seemed to regain its usual tone, but perhaps I just readjusted my expectations. For a while it seemed as if Luke’s daughter April had become ‘the new Rory’.

As for Lorelai, I’m convinced the writers don’t think much of this character, because Lorelai Gilmore’s faults seem magnified, somehow. She talks all the way through a lecture on Einstein’s theory of relativity at Yale University’s parents’ weekend. She’s not talking about astrophysics, by the way, but complaining that Emily has attended even though she’s not a parent but a grandparent. Earlier that day we saw Lorelai prepare for her trip to France by listening to a Teach-Yourself-French CD. Instead of attempting the actual French, she thinks it’s hilarious to speak the English in a mock-French accent, which I’m sure the French will think hilarious. By this point it’s cringeworthy. The writers could have done something more clever such as have Lorelai make a genuine mistake, or crack a French pun — after all, the character of Lorelai Gilmore is supposedly very smart.

HOWEVER. Honestly, Amy Sherman-Palladino, the writer who left at the end of season six, left season six in a mess. It was a difficult job for the writers of season seven to claw the plot back ‘on track’, and although the final episode was predictable, I felt that it tied everything up nicely. There was no ‘rescued by a rich boy’ kind of happy ending, and I have to admit I had been dreading that possibility.

SO IS IT ANY GOOD? QUALITY-WISE?

TV-wise:

The characters are exaggerations and the non-white characters are caricatures.

Small-town life is equally caricatured, and nothing important ever seems to happen without the whole town assembling, or pressing their noses against a window (quite literally, at one point in Luke’s Diner). In other words, if it doesn’t happen in front of an audience, it doesn’t have the same gravity. This is a narcissistic show.

On that point, the actors always look as if they’re performing on a stage. This is part of the style, and is partly due to the fast-talking, but can be annoying if naturalistic is your thing.

The usual cheap tricks of long-running sitcoms are employed. It annoyed me that they used the very same actress (who you may even recognise from Twin Peaks) to play two different characters.

Some scenes are definitely tighter than others. There’s no real suspense — this is coziness itself — and the cliff-hanger at the end of each season is of average intensity, usually revolving around relationship conflict. This elevates the role of the Gilmore girls’ relationships with men to an important plane, despite being outwardly a show about mothers and daughters and female friendships.

If you watch the episodes too close together, Lorelai’s relationship cycle is extremely irritating. PICK A MAN, ALREADY. OR DON’T. JUST DON’T.

For a younger audience:

There’s something very calm and embracing about the atmosphere of Stars Hollow and surrounds. This is pure, unthinking escapism. In that regard, Gilmore girls works, and it would also work for girls whose lives are far less stable and privileged than that of Rory Gilmore. It’s nice to pretend that we are Rory Gilmore, insofar as that leap is possible. The coziness might well have the opposite effect, of reinforcing to a girl in the opposite of Rory’s position just how lucky other people can be.

Rory Gilmore is a fairly rare character in that she is a smart, feminine girl who the audience sees actually studying. She doesn’t magically come up with all the answers behind the scenes, playing sidekick to two boys. Rory makes certain things cool: coffee, flowing dresses and reading for pleasure. Throughout seven seasons, Rory is shown reading a wide variety of books. Here’s the Rory Gilmore reading list. This show might even prompt a non-reading fan to pick up some of these books. (I’ve only read 27 of them, but I aim to read many more before I’m dead.)

What else to DO, after YOU WATCHED ALL OF THE Gilmore Girls?

You could watch Bunheads, but don’t get too into it because you will find it stops abruptly: The Cancellation of Bunheads: Why TV’s Most Underrated Show Deserved Better

![Bunheads (2012) Poster]()

There is, naturally, a Bunheads Wiki for true enthusiasts.

Or you could read Lauren Graham’s YA Book

![]()

Where Are They Now? — Lots of actors had small parts on Gilmore Girls and then made it big.

![]()

![]()